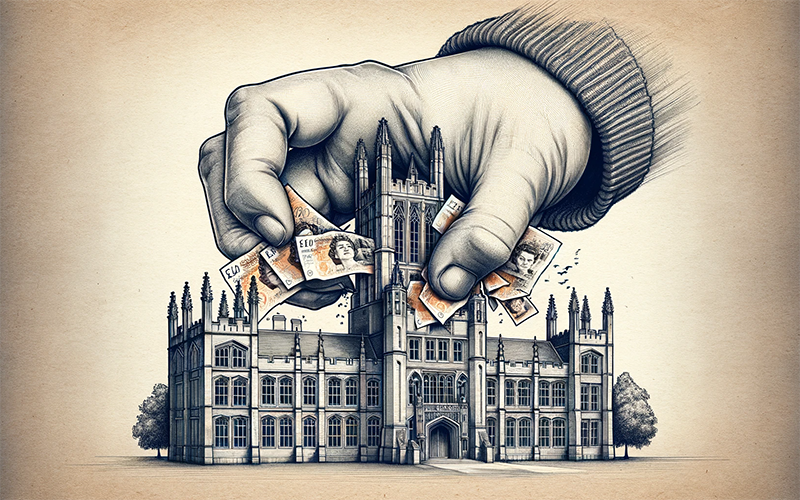

UK higher education is currently facing a financial crisis, with political inaction being a key driving force behind it.

In a move that raises eyebrows, politicians are shying away from the complex issue of the financial crisis in UK higher education, especially with an election looming. This avoidance has caused concern among Labour strategists who fear that the Conservatives are relegating these problems to the ‘too difficult’ basket, marked for another party to solve. However, this isn’t a one-sided scenario, and collectively politicians need to address these problems before they unravel to the point of no return.

The success and struggles of UK universities

The UK prides itself on its world-class universities. With institutions like Oxford, Cambridge, and Imperial ranking in the global top 10, and four others in the top 50, the UK outshines the rest of the EU in higher education. These institutions have long been magnets for international students and academics.

However, these prestigious universities are not without their challenges. There is a perception within the government, particularly among Conservatives, of an overemphasis on arts and humanities courses, which are deemed of limited economic value. The focus is shifting towards the need for more vocational skills.

The funding crisis

The heart of the matter lies in the deepening funding crisis. With tuition fees capped at £9,250 in England (£9,000 in Wales) and eroding under inflation, alongside diminishing research and teaching grants, universities are in financial turmoil. The Russell Group claims an average loss of £2,500 per domestic student in England last year. Similarly, Scotland faces tight budgets due to its different funding model. Additionally, there’s a shortfall in postgraduate research funding and increasing pressure from pension payments.

To cope, universities have relied on international students’ uncapped fees. However, recent immigration rule changes are causing a drop in applications, compelling some universities to lower entry requirements. A PwC UK Higher Education Financial Sustainability Report warns of deficits if the boom in foreign student recruitment ends, with anywhere from 51% to 80% of UK universities effected.

The complexities of UK higher education financing

The student loans system in England is also under scrutiny. Despite repayment rule changes, a significant portion of students will not fully repay their loans. The outstanding student loan debt is expected to balloon to £460bn by the mid-2040s.

Universities are campaigning for the £9,250 tuition fee cap to be index-linked, yet neither major political party is willing to consider fee increases. Meanwhile, Labour promises to reduce graduate debt without extra taxpayer costs, but how remains unclear.

The primary financial support for universities in the UK predominantly stems from the tuition fees levied on students. In addition to this, universities benefit from governmental grants distributed by the Office for Students, which, for the academic year 2022–23, amounted to £1.3 billion or approximately £1,000 per student, according to The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). Despite the one-off increase in the tuition fee cap since 2012, the inflation-adjusted value of these fees for domestic students has decreased by about 20% over the past ten years. Consequently, the funding available per domestic student for educational purposes has diminished by 16% since 2012, a trend expected to persist due to ongoing tuition fee freezes. In recent times, universities have encountered growing requests for financial aid from students, exacerbated by the diminishing real value of maintenance loans, without receiving significant extra funding from the government to cover these extra expenses.

To restore the real value of educational funding per student to its 2017–18 levels, it would be necessary to elevate the tuition fee cap by 23% to £11,370. This adjustment would result in an immediate increase of £2.6 billion in student loans for the cohort entering in 2023, though the majority of these costs are anticipated to be reimbursed by graduates. As a result, the long-term financial impact on the government would be minimised to £0.6 billion.

The scenario is different for international students, whose tuition fees are not bound by the same cap as domestic students and are generally much higher. Some universities have increasingly relied on funds from international student fees to compensate for the real-term decline in domestic teaching resources. This strategy, however, poses a risk of universities becoming overly dependent on international student enrolment and potentially displacing domestic students, especially if there are limitations on capacity in the short term.

The Office for Students is tasked with overseeing the financial health of higher education institutions in the UK. In its May 2023 review, the sector was deemed to be financially robust overall, though it pointed out several medium-term challenges. These include the pressures of inflation, the financial strains of attracting and supporting both students and staff, and a heavy reliance on the fees from international students.

Rethinking the approach to UK higher education

The current scenario begs several questions. Should students be excluded from immigration statistics, as the majority eventually leave the UK? How effective is the current student loans system, with its burden of decades-long debt for students and unrecoupable billions for the government?

One solution could be to raise or abolish the fee cap, creating a genuine market. However, this risks making higher education inaccessible to students from poorer families. An alternative is increased state grants for specific courses, but this comes with its own financial challenges.

The need for a new model

The most crucial question is whether the current higher education model serves society and individuals, especially when many graduates find their degrees don’t guarantee the careers they expected. Should there be a reduction in undergraduate places, encouragement for mergers, and a push towards more job-focused education? A look towards the US tiered model or support for an elite sector with higher funding, shifting the focus of the rest towards vocational skills, might be options.

These concerns are highlighted across various industries, perhaps no more so than within the engineering sector. As Rhys Morgan, Strategic Projects Director, Skills and Inclusion at the Royal Academy of Engineering adds: “We are concerned that the current level of UK student tuition fees and additional strategic priorities grant funding for high-cost, strategically important subjects, is not sufficient for universities to ensure sustainable provision of engineering degrees, particularly given recent inflationary pressures. As a result, we continue to see increasing reliance on international students to subsidise provision for UK students as well as costs of research. This exposes higher education institutions to external shocks and global competition. If the income is no longer available to keep courses viable across all current providers, then this risks reducing the number of places for UK engineering students when there is increasing demand for these skills across the economy.”

The way forward

As political parties plan beyond the election, they need to envision the future of higher education and how to preserve one of the nation’s competitive advantages. The questions are politically and socially challenging, but ignoring them could lead to more significant problems for the UK’s higher education sector.